Futurism, an avant-garde cultural and artistic movement, emerged in the early 20th century as a bold rejection of tradition and an emphatic embrace of modernity. Rooted in Italy but spreading across Europe, including Russia, Germany, and Britain, Futurism celebrated technology, speed, and industrial progress. It aimed to revolutionize society through art, while its influence spilled over into film, music, architecture and literature. With its ideals of dynamism and innovation, the movement found unexpected echoes in today’s Solarpunk, offering fascinating parallels and contrasts between past and future visions.[1][2]

Geopolitical Background

The early 20th century was a time of dramatic transformation. Europe was undergoing rapid industrialization, urbanization, and technological advancements. Automobiles, airplanes, X-rays and electricity were reshaping the way people lived, while political tensions simmered, culminating in World War I. In this context, Futurism became a response to a world oscillating between optimism for the possibilities of technology and anxiety over societal upheaval.

Inception

Italy, where Futurism was born, faced its own unique challenges. As an aspiring industrial power struggling with economic stagnation, the country provided fertile ground for the movement’s radical ideas. Futurism expressed the desire to cast aside Italy’s classical heritage and launch it into a modern, industrial age.

Futurism was officially launched with Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Manifesto of Futurism, published in Le Figaro in 1909. Marinetti glorified speed, energy, and technology, calling for the destruction of museums and libraries to cut ties with the past. The movement swiftly attracted artists from various disciplines, each adapting its ideals to their craft. Marinetti and other Futurists actively supported Italy’s entry into World War I, viewing it as a means to achieve national renewal. The emphasis on nationalism, militarism, and the aestheticization of politics resonated with the emerging Fascist ideology. After the war, Marinetti aligned himself with Benito Mussolini and the Fascist movement, even serving on the Fascist Central Committee at one point.[4]

Key Elements in Futurism

Futurist artworks, often paintings or sculptures, consistently emphasize dynamism: subjects are depicted in motion, never still. For instance, a dog might be shown with so many legs that they almost resemble propellers. This simultaneity of vision becomes a hallmark of Futurist paintings, immersing viewers as active witnesses to unfolding actions. Futurism arranges motion in visual arts, traditionally static by nature, through “lines of force.” These lines convey a certain directional significance, transforming their basic form to become spinning or centralizing forces. Objects, colors, and planes interact dynamically in a chain of “simultaneous contrasts,” capturing the essence of universal dynamism.

In Italy, Futurists like Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla created dynamic, fragmented works that emphasized motion. Russian Futurists, including Vladimir Mayakovsky and Kazimir Malevich, merged Futurism with revolutionary themes. German artists borrowed Futurist elements for Bauhaus architecture, while in Britain “Vorticism” emerged, a uniquely British take on industrial energy and geometry.[2]

Futurism in Film and Music

Futurism’s fascination with modernity naturally extended to film, a new art form that mirrored the movement’s love of speed and innovation. Futurist cinema sought to break with narrative conventions and create purely visual experiences. Although many of these early experiments are lost, films like Arnaldo Ginna’s Vita Futurista (1916) captured the movement’s ethos with its fragmented, experimental storytelling.

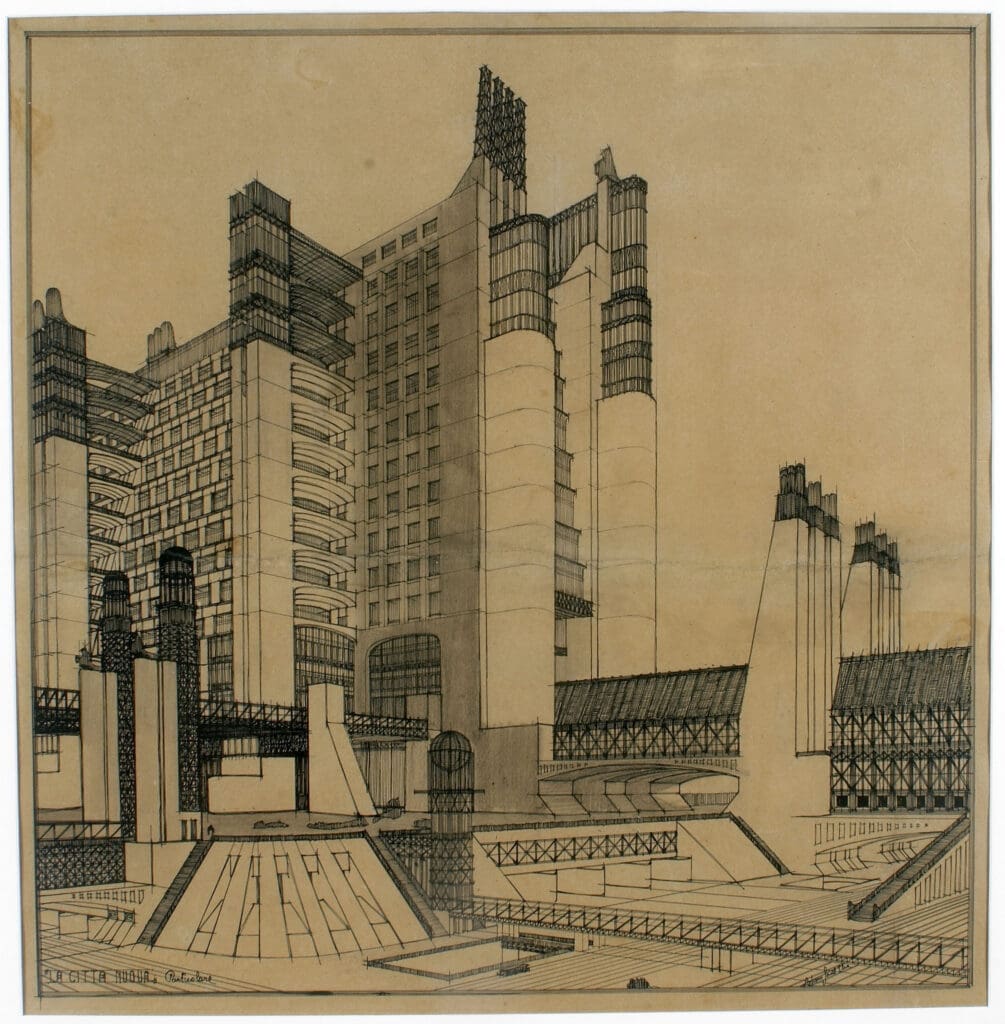

The movie Metropolis also exhibits significant influence from Futurist ideals. The film’s futuristic cityscapes, with their towering skyscrapers, mechanized factories, and bustling urban energy, mirror the Futurist obsession with modernity, technology, and industrial progress. Futurism’s celebration of machines and dynamism is particularly evident in the film’s depiction of the massive, omnipotent machinery driving the city’s economy. The sleek, geometric aesthetics of the architecture evoke Futurist visions, like Antonio Sant’Elia’s La Città Nuova, while the film’s pulsating, rhythmic editing recalls the kinetic energy celebrated in Futurist art and manifestos.

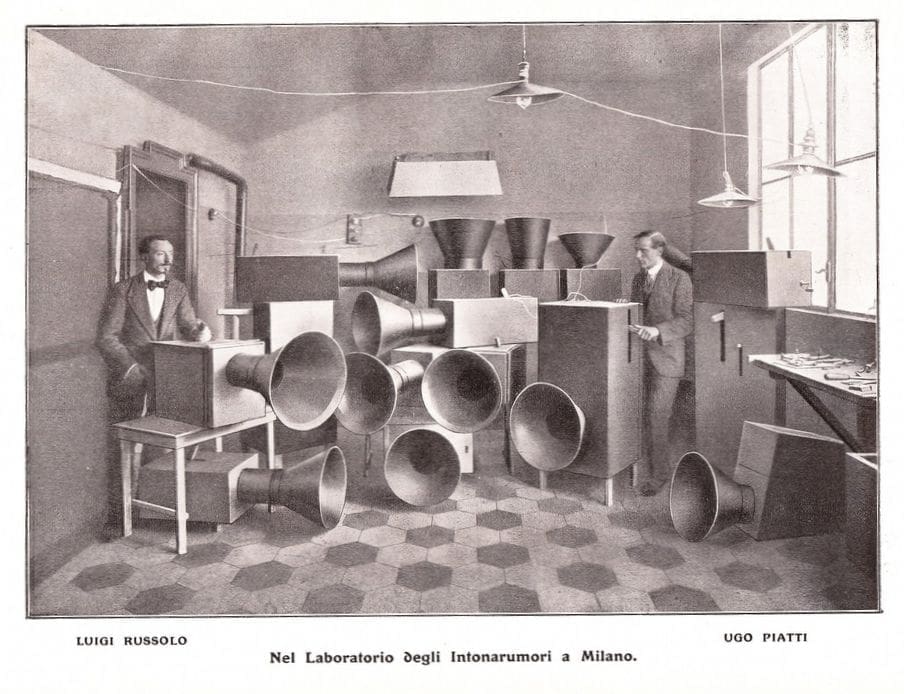

In music, Luigi Russolo, a central Futurist figure, wrote The Art of Noises (1913), a manifesto advocating for the use of industrial sounds in music.[5] Russolo’s intonarumori—noise-generating machines—created compositions mimicking the sounds of factories, machines, and urban life. They were the first mechanical “Synthesizers”, laying the groundwork for electronic and experimental music genres that emerged in the following decades.

Artistic Evolution Across Disciplines[1]

Sculpture: Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913): Umberto Boccioni’s iconic sculpture capturing dynamic movement. You can see a little version of it on every Italian 20 cent Euro-coin

Painting: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912): Giacomo Balla’s innovative depiction of motion

Architecture: La Città Nuova: Antonio Sant’Elia’s visionary urban designs powered by technology

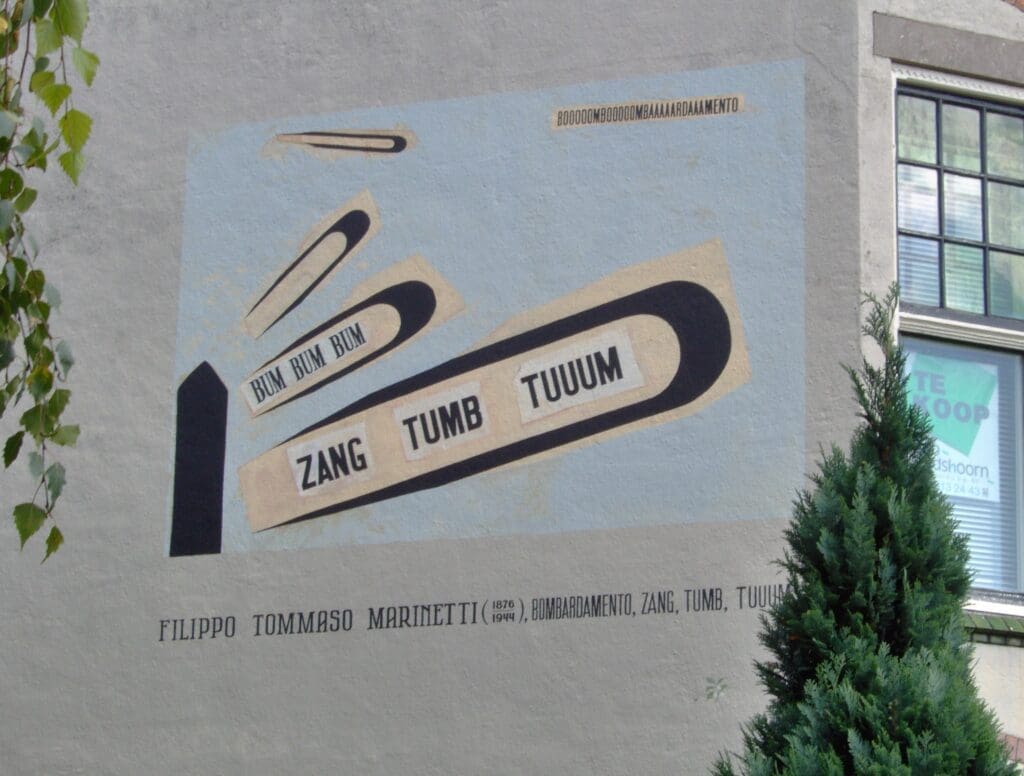

Literature: Zang Tumb Tumb (1914): Filippo Marinetti’s experimental poetic exploration of war and modernity

Music/Engineering: The Intonarumori: Luigi Russolo’s noise machines expanding the boundaries of music

Public Reception and Legacy

Futurist exhibitions, including the 1912 touring show across Europe, sparked intense debate. Critics admired the movement’s innovation while others dismissed it as overly aggressive. The public was divided—some embraced Futurism’s vision of modernity, while others found its violence and rejection of tradition unsettling.

Futurism and Solarpunk: Touch Points and Contrasts

Futurism and Solarpunk share the overarching goal of envisioning a transformative future, one powered by human ingenuity and technological advancements. Both movements seek to push boundaries, but their ideals and values differ profoundly. Futurism, born in the industrial era of the early 20th century, celebrated the aggressive march of modernity, often through its association with urbanization, speed, and the power of machines. Its supporters glorified conflict, even viewing war as a purifying force and a tool for societal renewal. War was embraced as a method to clear away stagnation and establish dominance, reflecting Futurism’s fascination with destruction and renewal.

Solarpunk, in contrast, avoids any semblance of violence, advocating instead for collaboration and coexistence. Solarpunk envisions a sustainable future rooted in ecological balance, renewable energy, and community-driven solutions. Where Futurism sought to dismantle tradition entirely, Solarpunk’s approach is to blend historical knowledge—such as traditional craftsmanship and ecological wisdom—with innovation, creating green communities that thrive in harmony with nature. This stark difference highlights how one movement idealizes conflict and dominance, while the other champions peace and symbiosis.

Conclusion

Although its philosophies were divisive, Futurism showcased the immense power of creative vision to drive change. Its energy-infused works of art continue to inspire to this day.

Rebellion, non-conformity, and the challenge to societal norms were central to the 1970s Punk movement and remain key elements of the Solarpunk movement as well—including its naming convention. Solarpunk offers an alternative narrative for shaping the future, rooted in harmony rather than conflict, providing hope for a peaceful transition to sustainable living.

These movements, despite their stark contrasts, both represent humanity’s deep-seated aspiration to forge a better tomorrow—whether through bold confrontation with the past or peaceful integration of tradition into a sustainable future.

Sources:

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Futurism

[2] https://www.theartstory.org/movement/futurism/

[3] https://www.britannica.com/art/Futurism

[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filippo_Tommaso_Marinetti

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luigi_Russolo