Geothermal energy is the practice of harvesting Earth’s internal heat and turning it into usable power and heat. In Solarpunk terms, it’s the gentle, always-on counterpart to sun and wind: less visible, extremely constant, and deeply compatible with urban life because it can run invisibly under streets, parks, and tram lines.

Terminology

At its simplest, geothermal is heat moving from hot rock toward the cooler surface. We “plug in” to that flow in different ways depending on depth and temperature: shallow systems circulate fluids through buried pipes to provide efficient heating and cooling (using the ground as a heat sink), deeper resources tap hotter rock for district heating and industrial process heat, and the hottest reservoirs can generate electricity directly.

Binary-cycle plants allow geothermal electricity generation even when the underground heat is not hot enough to produce steam directly, by using a secondary fluid that boils at lower temperatures than water.

Geothermal in Practical Terms

There are three big “families” of geothermal use:

Deep geothermal for electricity and district heating: Wells reach hot permeable formations and bring hot water or steam to the surface. The heat can be delivered directly into district heating networks for buildings and industry, or—at higher temperatures—used to generate electricity, either by flashing steam to run a turbine or by passing heat through a binary-cycle plant using a secondary fluid that boils at lower temperatures.

Direct-use heat and district heating: If the resource is hot enough, you can skip electricity and deliver heat straight into a network: apartment radiators, domestic hot water, greenhouses, public baths, and industrial facilities.

Shallow geothermal with heat pumps (ground-source): A loop of pipe in the ground such as vertical boreholes or horizontal trenches exchanges heat with stable subsurface temperatures. Heat pumps concentrate that heat for buildings in winter, and reverse for cooling in summer. This is geothermal as building-scale infrastructure — quiet, modular, and extremely city-friendly.

Capacity, Now and Tomorrow

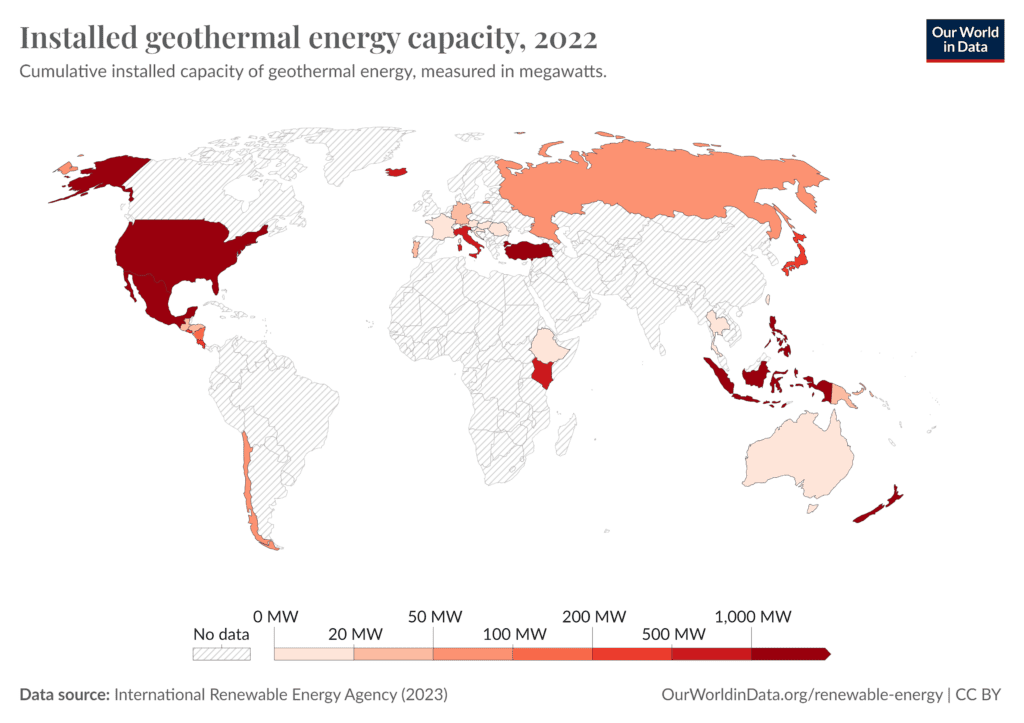

Today’s installed geothermal electricity capacity is still modest compared with wind and solar: Global Energy Monitor reports global installed geothermal capacity reached 16.2 GW (March 2025 figures).[1] That number understates geothermal’s importance in cities, since much of its contribution lies in decarbonizing heating — displacing gas boilers via district heating networks and heat-pump systems. The upside is that geothermal is not constrained by weather and time of day.

The International Energy Agency argues that with continued technology improvements, including techniques borrowed from oil and gas drilling, geothermal could scale dramatically, up to 800 GW of cost-effective geothermal power capacity by 2050 in a high-innovation pathway.[2] That’s not a guarantee, but it’s a credible upper-bound scenario from a major energy institution.

On raw physical potential, the ceiling is enormous. The IPCC’s geothermal chapter estimates technical potential for electricity generation between 118 EJ/yr (to ~3 km depth) and 1,109 EJ/yr (to ~10 km depth), with EJ (exajoule) equal to one quintillion joules.[3] Real-world deployment is limited by economics, drilling risk, permitting, and local geology — but the planet’s heat itself is not the limiting factor.

Re-use of Geothermal in a Solarpunk City

Solarpunk cities win when they turn “waste” into commons: waste heat into warmth, old infrastructure into new systems, and daily necessities into shared services.

Geothermal fits this logic in three ways:

Continuous circular and natural flow: Unlike fuels that are consumed, geothermal systems circulate and exchange heat. When managed well with reinjection and reservoir monitoring, the resource can be long-lived.

Re-using urban networks: we already know how to build pipes, heat exchangers, district loops, and neighborhood-scale energy hubs. This is especially powerful in Europe where district heating already exists in many cities, and where retrofitting buildings is easier when the heat source is centralized.

Geothermal applies skills and tools from the fossil era without keeping fossil outcomes. Modern directional drilling, subsurface imaging, and high-temperature materials—refined in oil and gas—can be repurposed to build clean baseload heat and power.[4]

In Germany specifically, the case is even clearer: Fraunhofer IEG’s roadmap estimates that Germany’s heat potential from deep geothermal is well over 300 TWh per year, equivalent to around 70 GW of installed capacity.[5] This could cover approximately 25% of Germany’s heat demand, which is significant given its 83 million population.

Geothermal paves the way for mega-scale solutions!

Practices for “Plugging in” to Geothermal

District heating first, electricity where it fits: In many places, geothermal heat is easier and cheaper than geothermal electricity because you can use lower temperatures effectively. Cities can prioritize replacing gas boilers in district networks, then add electricity generation where resources are hotter or where binary-cycle plants make sense.

Heat-pump amplification: Shallow geothermal plus heat pumps can turn modest ground temperatures into high-value building heat. Pairing heat pumps with geothermal district loops can reduce peak electricity stress while squeezing more utility from each meter of borehole.

Cascaded use: Use the hottest resource for electricity first, then deliver the “leftover” heat to district heating, then use the cooler return for greenhouses, aquaculture, or absorption cooling. This is how you turn one wellfield into multiple civic services.

Closed-loop and advanced systems: Where permeability is poor or seismic risk is a concern, closed-loop systems circulate fluid through sealed wells to harvest heat without moving formation fluids. These approaches are rapidly developing.[6]

Geothermal projects can carry seismic risks if drilling or fluid injection alters underground stresses, especially in fractured rock. A well-known example is Staufen in Germany, where geothermal drilling in 2007 triggered ground uplift and minor seismic effects, damaging buildings and highlighting the need for careful geology, monitoring, and regulation.

Operational Geothermal Plants

Germany Munich region deep geothermal feeding electricity and heat: In the Munich area, geothermal is becoming a backbone strategy. The geothermal plants are located in the Bavarian Molasse Basin, one of Europe’s most important deep geothermal regions.

A concrete example is the cluster of plants associated with Stadtwerke München (SWM). Geothermal plants at Dürrnhaar and Kirchstockach (operating since 2012) have an overall electrical output of 11 MW.[7] That’s steady renewable electricity, not dependent on weather. SWM’s Sauerlach geothermal plant has an installed electric capacity of 5 MW and thermal capacity of 4 MW.[8]

Iceland, Hellisheiði, a model of combined electricity and hot-water infrastructure: If you want to see geothermal as civic-scale normality, Iceland is the prime example. The Hellisheiði Power Plant supplies both electricity and district hot water; the operator ON Power states it has 303 MW of electricity capacity and 200 MW thermal capacity.[9] That thermal stream is not a side benefit, it is the city service: hot water for heating across the capital region. Hellisheiði demonstrates a Solarpunk aspect based on on its infrastructural design: minimal land footprint relative to output, stable baseload generation, and a direct relationship between a public need (warmth) and a local resource (subsurface heat).

Kenya, Olkaria, geothermal as national resilience and grid stability: Kenya shows how geothermal can anchor a rapidly growing grid with dependable power. KenGen’s official geothermal page reports its geothermal plants have a combined generation capacity of 799 MW.[10] Within the Olkaria complex, specific stations carry large, dispatchable capacity. For cities, this matters because grid stability is a public good.

Geothermal as Steady Grid Supply

From a Solarpunk perspective, this is the “plug”: wells draw constant heat from underground, convert it into electricity and usable warmth, and circulate it through local power lines and heating networks — quietly and discreetly, year after year.

Geothermal provides this baseload supply, with far less need for energy storage than, for example, battery energy storage system (BESS) solutions. It delivers steady electricity for transport, heating, and industry without requiring a fossil or nuclear “backup.”

Solarpunk Takeaway

Geothermal is not the loud hero of the renewable story. It’s the underground civic utility that makes everything else easier: cleaner district heating, steadier grids, and neighborhoods that can be warm without combustion. Its present-day global electricity footprint is still small, however, its plausible growth is huge. Solarpunk citizens “plug into” the Earth not to extract and burn, but to circulate and share: wells, pipes, heat exchangers, and public networks that turn geological eons into everyday energy supply and comfort.

Sources:

[1] https://globalenergymonitor.org/projects/global-geothermal-power-tracker

[2] https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-geothermal-energy/executive-summary

[3] https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/Chapter-4-Geothermal-Energy-1.pdf

[4] https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-geothermal-energy

[5] https://www.ieg.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ieg/documents/Roadmap%20Deep%20Geothermal%20Energy%20for%20Germany%20FhG%20HGF%2010102022.pdf

[6] https://www.iea.org/reports/the-future-of-geothermal-energy

[7] https://www.tiefegeothermie.de/top-themen/mehr-regenerativer-strom-fuer-muenchen-swm-kauft-zwei-geothermieanlagen

[8] https://geodh.eu/project/bavaria-sauerlach/

[9] https://www.on.is/en/virkjanasvaedi

[10] https://www.kengen.co.ke/index.php/business/power-generation/geothermal.html